THE STORY OF THE SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS REGION

Prepared for the Shawangunk Mountains

Scenic Byway Steering Committee

By Wendy E. Harris

INTRODUCTION

The story of the Shawangunk Mountains Region (the region) is the story of two valleys and the mountain that lies between them. This mountain—known as the Shawangunk Ridge, or sometimes just "the ridge"—and the Wallkill and Rondout Valleys, share a history that begins about 11,500 years ago, at a time when the last glaciers were receding from the landscape and the first human beings began to venture into what is now New York State. For countless generations, Native Americans lived here, traveling back and forth over the Shawangunk Ridge, between the two rivers that give the valleys their names. When first encountered by Europeans in the early 17th century, the resident Native American groups, known as the Esopus, were united by a common culture. So too were the Dutch and French Huguenot settlers who supplanted the Esopus and whose descendents reside in the region to this day. The degree to which these groups once dominated the region is evident in the abundance of local place names deriving from their languages. Although the ridge would remain largely uninhabited throughout the pre-industrial period, its presence shaped patterns of settlement and travel, as well as local lifeways and livelihoods.

In the early decades of the 19th century, with the advent of industrialization and new forms of transportation, the story of the region becomes more complex. At times during the next century and a half, the histories of the Rondout and Wallkill Valleys diverged, each following slightly different social and economic paths. Throughout this period, however, the ridge remained a powerful force in a local economy driven by the region's natural resources and by tourism. Today as the 21st century opens, the unbroken forests of the Shawangunk Ridge and the scenic farmland and villages of the two valleys, although threatened by development, have become critical aspects of the region's identity. This shared experience, and the awareness that these are valuable resources that must be protected, has had the effect of bringing together communities and institutions from both sides of the ridge. The region's multiple stories are converging once again into a single unified tale.

THE SETTING

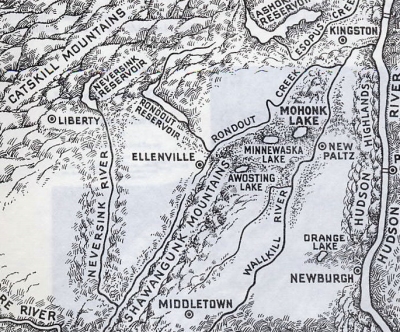

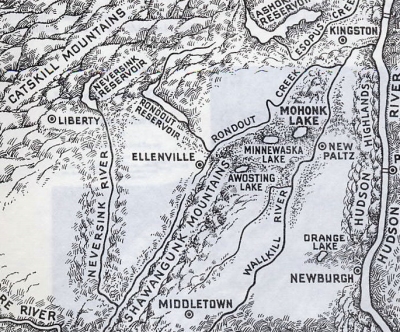

The route of the Shawangunk Mountains Scenic Byway (the byway) binds the region together. The network of roadways defining the byway encloses a group of communities that at various times in their histories have been affected by their proximity to the ridge. At the center of the region lie the Northern Shawangunks, part of a larger ridge system that extends for 350 miles from the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania northwards to Rosendale, New York. Known in Pennsylvania as the Blue Mountains, in New Jersey as the Kittatinnys, and in New York as the Shawangunks, the ridge is a subsection of a geological province known as the High Allegheny Plateau. Within the region, the topography of the larger ridge system assumes its most dramatic and rugged aspect, with white cliffs, sky lakes and deep fissures in the conglomerate bedrock known as "ice caves."

Most of

the region lies within Ulster County. A small section is located within

Orange County. The southernmost point of the region is Bullville,

located in the Town of Crawford, Orange County. The region's western

boundary is the Catskill Mountain foothills, forming the western margin

of the Rondout Valley. The Rondout Creek flows through the valley, fed

by tributaries rising in the Shawangunks and in the foothills of the

Catskills. Entering the valley from the west at Napanoch, the Rondout

meets

the Sandburgh Creek and is eventually joined by the Wallkill River near

the Village of Rosendale, Ulster County—the region's northernmost

point.

Near Kingston, the Rondout Creek flows into the Hudson River. The

region's

eastern boundary overlaps and extends slightly to the east of the

Wallkill

River. This river, which is the principal drainage for the Wallkill

Valley,

flows north, originating in northern New Jersey.

Most of

the region lies within Ulster County. A small section is located within

Orange County. The southernmost point of the region is Bullville,

located in the Town of Crawford, Orange County. The region's western

boundary is the Catskill Mountain foothills, forming the western margin

of the Rondout Valley. The Rondout Creek flows through the valley, fed

by tributaries rising in the Shawangunks and in the foothills of the

Catskills. Entering the valley from the west at Napanoch, the Rondout

meets

the Sandburgh Creek and is eventually joined by the Wallkill River near

the Village of Rosendale, Ulster County—the region's northernmost

point.

Near Kingston, the Rondout Creek flows into the Hudson River. The

region's

eastern boundary overlaps and extends slightly to the east of the

Wallkill

River. This river, which is the principal drainage for the Wallkill

Valley,

flows north, originating in northern New Jersey.

The Shawangunk Ridge is the dominant landscape feature of the region. Through time, its physical presence has had a profound influence upon the region's evolution. Although the story that follows below is regional in scope, its focus is necessarily upon the geological, natural, and cultural history of the Shawangunks.

GEOLOGY AND VEGETATION

Most of the natural resources that we enjoy today and that were exploited in the past by Native Americans, Euro-American settlers, and other previous inhabitants of the region, have their origins in the unique geology of the Shawangunk Ridge. The most visible geological feature of the ridge is the white rock that forms its "backbone." Caught by the sun at certain angles, the Shawangunks seem to glow from within. In the 17th century, the Dutch, searching for minerals that they believed lay in the wilderness west of the Hudson River, spoke of a "crystal mountain" (Anonymous 1907a). It was probably the Shawangunk Ridge.

Geologists call the ridge's caprock "the Shawangunk formation." Contained within it are layers of sandstone, siltstones, shales, and—most notably—a hard white conglomerate rock known as "Shawangunk grit" or Shawangunk conglomerate." This conglomerate is the layer that is most exposed and visible throughout the ridge. An extraordinarily resilient rock, it is made of quartz pebbles bound together in a cement-like matrix of white sand. Over the millennia it has resisted the effects of erosion by water and glaciation. Its formation dates to a time designated as the Silurian Period by geologists - about 420 million years ago. Originating as erosional sediments washed from the slopes of an ancient mountain chain ancestral to today's Taconic Mountains, the conglomerate was deposited in braided rivers that flowed into an inland sea. This shallow Silurian Period sea became deeper during the Devonian Period (345 million years ago to 395 million years ago). Subsequent layers of fossil-rich limestone accumulated above the Shawangunk conglomerate. Below the entire Shawangunk Formation was a 10,000-foot thick layer of compacted mud and silt known as the Martinsburg Formation. It was formed from deep ocean deposits during the Ordovician Period, approximately 465 million years ago. In contrast to the hard white conglomerate, the Martinsburg shale is grayish brown in color and easier to erode. Tens of millions of years of mountain building and erosion are represented in the unconformable contact between the two formations (Davis 2003: personal communication; Fagan 1998: 11-23; Kiviat 1988: 3-8; Snyder and Beard 1981: 8-12; Van Diver 1985).

Approximately 330 to 280 million years ago, the entire Shawangunk Formation was affected by a sequence of folding and faulting known as the Alleghenian Orogeny. At this point in geological history, the general topography that we would eventually recognize as the Shawangunk Ridge and the adjoining valleys took shape. Because all of this rock remained buried beneath layers and layers of sediments, the process also involved the uplifting and exhumation of the Shawangunk formation and underlying formations. The actual emergence of the ridge occurred during the last 100 million years, when subsequent erosion of overlying rock revealed the erosion resistant Shawangunk conglomerate (Davis 2003, personal communication).

Beginning about two million years ago a great ice sheet lying to the north began a series of advances and retreats, burying the Shawangunks in ice that was at times as much as a mile deep. The erosive forces of glaciation sculpted the terrain that we see today. Overlying soils, as well as the remaining softer limestones and underlying shales, were removed, leaving jagged escarpments and bare ridge tops composed of durable conglomerate. The Shawangunks' sky lakes (Maratanza, Mud Pond, Awosting, Mohonk, and Minnewaska) are also a legacy of the glaciers—created when water pooled in deep basins quarried by ice into the bedrock's surface. During glaciation and afterwards, weathering of the conglomerate formed the crevices, pinnacles, and sharp cliff faces that comprise the familiar Shawangunk landscape. Even today, weaker shales exposed at the base of the cliffs are continually eroding away, causing more breakage above, and thus sharpening the already dramatic contours of the conglomerate formations above (Davis 2003, personal communication; Kiviat 1988).

Glacial and post-glacial events also modified the two valleys adjoining the ridge. For millions of years, stream flowing from the Catskills and the Shawangunk Ridge carved out the Rondout Valley from Devonian limestones, shales and siltstones that formed the north and west sides of the Shawangunks. The legacy of the advancing and retreating ice sheet here is mostly depositional. The flatness of the central valley floor is due to glacial outwash and sediments deriving from extinct glacial meltwater river and lakes. In the Wallkill Valley, the very fractured shales and siltstones forming its bedrock were easily eroded by the passage of the ice. As the ice retreated north up the Hudson Valley, the Wallkill Valley served as a basin for a series of extinct glacial lakes. There was a time when the view from the Shawangunk Ridge was of vast lakes on either side, and of a wall of white ice melting back towards present day Albany (Davis 2003, personal communication; Fagan 1998: 1-23; Isachsen et al. 2000, Van Diver 1985: 91, 124-125).

The highest points in today's Northern Shawangunks range from about to 1000 to 2200 feet above sea level, as opposed to the valleys lying to its east and west which average about 250 feet elevation. Covering the ridge is an array of vegetation as distinctive as the underlying geology. The ridge contains a variety of natural communities including: cliff, talus, and ice cave communities; extensive northern hardwood forests; the largest chestnut oak forest in New York State (30,000 acres), approximately 7000 acres of pitch-pine-oak heath rocky summit; and the globally rare dwarf pine ridge community. Found within these communities are 33 rare plant, animal, and nonvascular species (Batcher 2000: 5). The sheer scope of the Shawangunks' biodiversity elements, along with its geological inheritance, makes it one the most compelling landscapes in the world.

The ridge's unusual plant life is very much a product of the underlying Shawangunk conglomerate. Harder even than granite, the conglomerate has weathered very slightly since the last glaciation, producing the thin, nutrient poor, acidic soils that support pitch pines and other forms of plant life characteristic of the ridge's unique environment. Interspersed with these conglomerate-derived soils are other markedly different soil types originating from glacial tills, shales, limestones, and the more recent breakdown of organic matter. As the naturalist Erik Kiviat (1988: 14-15) explains, the result is: "a fine-scale mosaic of topography and soil types that are related to the considerable variety in the habitats available to plants and animals." Other adaptational influences include high elevations and frequent fires.

The geologic and natural history of the Shawangunks has greatly affected the region's cultural history. As will be described below, it was not just the availability of the ridge's resources—such as animal skins, limestone, huckleberries, and timber—but also the very fact of the ridge's physical presence that would prove so influential to the people and communities existing within its sight.

THE NATIVE AMERICAN PERIOD (11,500 B.P. - Mid-17th Century)

Most of what we know about the region's Native American inhabitants comes to us from the work of archaeologists. Between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago, the last glaciers had withdrawn from our region (Fagan 1998: 22). In approximately 11,500 B.P. (before the present time) the first human beings began to move into the Hudson and Delaware River Valleys. Archaeologists call these people Paleo-Indians. Archaeological evidence of this culture, generally assigned dates of 11,500 to 10,000 BP has been found in the region, near the village of Wallkill (Eisenberg 1976: 111; 1991:165; New York State Museum Site Files). As indicated by archaeological remains, subsequent Native American cultures in the region include the Archaic (10,000-3,700 B.P), Transitional (3,700-2,700 B.P.) and Woodland Periods (2,700 B.P- 400 B.P.) (Eisenberg and Perez 1981; Funk 1976; Diamond 1995; Lindner 1998). Because so many of these sites are located within the flood plains or on the adjoining uplands of the Rondout and Wallkill Rivers, archaeologists believe that for thousands of years Native American settlement patterns were shaped by waterways. Such environments would have served as travel and trade routes, fishing areas, pathways for following game, and finally, with the advent of horticulture, sites for cultivation (Funk 1976). At the time they were first viewed by Europeans, the Wallkill and Rondout Rivers were said to be “lined with corn-planting grounds" (Sylvester 1880: 11).

Several lines of evidence, including archaeological sites, indicate a Native American presence on the ridge (Eisenberg 1976, 1991; Diamond 1995; Harris 2001a,b; Schrabisch 1936). Tools unearthed at the Mohonk Rock Shelter, in what is now the Mohonk Preserve, have led some archaeologists to assign dates as early as the Paleo-Indian Period (11,500 to 10,000 BP) to this site. They suggest that the ridge, because it may have been deglaciated earlier than the surrounding lowlands, would be an especially attractive area for the region's original inhabitants (Eisenberg 1991: 16). Regardless of their antiquity, the artifactual contents of the excavated sites indicate that over the centuries Native Americans ventured into the Shawangunks for various purposes including: hunting; gathering of various foodstuffs such as berries, nuts, and perhaps medicinal plants. Possibly they came for spiritual reasons as well. Their participation in the ridge's ecological processes is suggested by fossilized pollen samples. Beginning in about 1600 B.P., pitch pine dominance greatly increased, possibly encouraged by the Native American practice of setting forest fires in order to promote blueberry bush growth (Laing 1994, cited in Fried 1998: 25).

As it was later for the region's Euro-American settlers, the Shawangunk Ridge must have been an important landmark in a world of footpaths and rivers, visible from the Hudson River as well as from the mountains lying to the west. Native American travelers would have followed a number of trails over the ridge as they journeyed between the Wallkill and Rondout Valleys. One such footpath, the “Old Wawarsing Trail,” connected Native American settlements on either side of the mountain. Providing access from the Wallkill Valley westwards across the ridge top to the Rondout Valley, the trail crossed the steep eastward facing escarpment at a break near Indian Cave, passed close by Lake Awosting, and finally reached the Rondout River floodplain just outside of the Hamlet of Wawarsing (Fried 1995: 37-39, 2000: personal communication). The alignments of other trails became the basis for many modern roadways including Route 209, Route 52, and Route 44/55 (Historical Perspectives 1991: 18; Pritchard 2002: personal communication).

Although researchers often hypothesize using archaeological, linguistic and ethnographic evidence, we still lack much basic information concerning the cultural life of the region's Native American population prior to the arrival of Europeans. In fact, it is not until the middle of the 17th century—about twenty years after the first visits to the confluence of the Hudson River and the Rondout Creek by Dutch traders—that Ulster County's Native American residents begin to appear in written records (Fried 1975: 14-15). These men and women belonged to a Munsee-speaking branch of the Lenape who had come to be known as the Esopus. Sub-groups of the Esopus residing in our region included the Warranawongkongs and the Wawarsing (Goddard 1978; Pritchard 2002). The grand council house of the Esopus is said to have been located in Wawarsing (Sylvester 1880:20, 22).

THE PRE-INDUSTRIAL ERA: EXILE OF THE ESOPUS PEOPLE AND SETTLEMENT OF THE REGION BY EURO-AMERICANS (Mid-17th Century - Late 18th Century)

Earliest Settlement

The first Europeans to settle in what is now Ulster County arrived in Kingston in the early 1650s. Although we are now accustomed to defining the region's early settlers as “Dutch,” only a portion actually came from the Netherlands. This group, in fact, encompassed a heterogeneous mixture of French, Walloon, German, Flemish, Scandinavian, and English heritage, leading some researchers to refer to them as "Dutch-German-Huguenot" (Cohen 1992; Hansen 1995).

In many respects the Europeans' relationship to the region's landscape was very similar to the Esopus. Like the Esopus, the early settlers frequently relied upon rivers and streams to get them to their destinations. The earliest recorded visit to the region by Europeans probably occurred in 1660. In May of that year, a group of Dutch soldiers set out from Kingston and followed the Rondout Creek past its confluence with the Wallkill, just to the north of the village of Rosendale, and possibly continued as far as south as Accord (Fried 1975: 38-39, 174-177). Ultimately, European settlers would develop communities within the Rondout and Wallkill River Valleys, clustered along important trails and the corridors created by the two rivers. In most cases, the region's major Euro-American villages stood upon or adjacent to the sites of former Native American settlements (Parker 1922: 704-705.

The Rondout, as one of the principal tributaries of the Hudson River, first caught the notice of early European visitors and traders during a period when travel was restricted to the waterways lying between Fort Orange (Albany) and New Amsterdam (New York City). The confluence of the Hudson and Rondout was described in ship captain David DeVries' 1640 journal. He wrote: "The 14th May (1640) took my leave of the commander of Fort Orange, and the same day reached Esopers [sic], where a creek runs in, and where there is some maize land upon which some savages live"(Quoted in Fried 1975: 14). In fact, about one thousand Warranawongkongs lived here. This Esopus band called their settlement, Atharhacton, or “great field” and had more than 200 acres of fields under cultivation (Fried 1975: 179; Pritchard 2000: 243).

The Dutch settlement at Kingston was known as Wildwyck. In 1661 another settlement was initiated slightly to the south, called Nieuwe Dorp. It would become Hurley. The settlers quickly established farms and soon were growing sufficient amounts of corn, wheat, barley, and oats to supply not only their own needs but to ship down the Hudson River to market in New Amsterdam (present day New York City) (Schoonmaker 1888: 21-22).

The Esopus Wars and their Aftermath

During these first years, the settlers and their Native American neighbors attempted a peaceful coexistence. These efforts, however, were almost immediately doomed by conflicting concepts of land ownership, the destruction of the Native American's crops by the settlers' livestock, the subsequent retaliatory killing of livestock by the Native Americans, and the settlers' sale of liquor to the Native Americans (Fried 1975: 24; Hauptman 1976: 151). Tensions culminated in the First and Second Esopus Wars, spanning the years 1659 to 1664, which were fought throughout what is now Ulster County. Both sides committed terrible atrocities. Ultimately, however, it was the Esopus who suffered the most, losing food supplies and access to their cornfields, as well as much of their land. Reports immediately following the Second Esopus War indicate that the Esopus were dispersed and hungry (Fried 1975: 72-73, 108-111).

During the wars, the Dutch pursued the Esopus down the Wallkill and the Rondout Rivers, deep into the interior of what is now the region. It was during these expeditionary journeys that the Dutch may have first fully grasped the region's enormous agriculture potential. English forces had conquered New Netherland in 1663 and the parceling out of this territory by the provincial government began shortly thereafter. There was no resistance when the Dutch garrison at Wildwyck was replaced with British troops in 1664. The local officials were allowed to remain in office although the military leadership was now English. Governor Nicolls awarded the English soldiers at Kingston portions of the lands within present day Marbletown in 1668. This represented the first movement of Euro-Americans into the hinterlands of what was to become Ulster County (Fried 1975: 126-127; Zim 1946: 17).

As European settlement spread southwards down the Rondout and Wallkill Valleys, the Esopus people were gradually dispossessed of their lands. Driven from their fields and settlements, many of the Esopus may have taken up residence temporarily in more remote upland settings such as the slopes of the Shawangunks as well as to the west, within the Catskill foothills. Documentary evidence, however, indicates that the Esopus continued to function as a political and cultural unit during the first half of the 18th century, holding annual peace conferences at Kingston, (Fried 1975: 118-119; Ruttenber 1872: 201). The last of these occurred in 1771, most of the Esopus having been forced westwards into upstate New York and Ohio (Kraft 1986; Ruttenber 1872).

The region's original inhabitants left behind archaeological remains, the routes of early roadways, and words for villages, lakes, waterways, and mountains. The latter are perhaps the most lasting reminder of the Esopus and include such familiar place names as Mohonk, Kerhonkson, Wawarsing, Napanoch, and Pakadasink (or Papanasink) (Ruttenber 1906: 140-170). Archaeologists, linguists, and historians still debate the derivations of these words (Fried 1975; Pritchard 2002). Even the origins of "Shawangunk" remain obscure. Although certainly a Native American place name, it originally referred to a district near the present day Bruynswick, in the Town of Shawangunk. Eventually usage of “Shawangunk” spread from the Wallkill Valley to encompass the nearby ridge. In the 1680s, however, when references to the ridge first began to enter the documentary record, the ridge was not called Shawangunk, but rather was described as “the high hills …Pitskiskaker and Aisoskawasting” (Ruttenber 1907: 53). The Esopus, some researchers suggest, had no name for the ridge itself, only for particular locations within the ridge's bounds (Ruttenber 1907: 19).

Euro-American Cultural Traditions and Settlement Patterns

By the beginning of the 18th century, Dutch-American farms and villages had completely transformed the lands of the Esopus. Although the English had conquered New Netherland in the 17th century, Dutch architecture, religion and language were pervasive throughout the region well into the middle third of the 18th century. Even New Paltz's French Huguenots came to speak Dutch before switching over to English at the end of the century (Junior League 1774: 19). The Dutch also brought with them the practice of slave owning, with the result that a significant portion of the early population of the region was composed of people of African descent (Roberts 1977b; Roth 2001; Zim 1946). Reinforcing Dutch-American and French Huguenot cultural traditions were ties of kinship that spread across the region. The path of migration—southward form Kingston down the Wallkill and Rondout River Valleys, as well as across the Shawangunk Ridge—along with intermarriage among members of the old families, created webs of relationships that bound the region together. Family names such as Bevier, Deyo, Dubois, Hasbrouck, Van Keuren, and Van Wagener were common in communities on both sides of the ridge, many persisting into the present. Dutch place names also endure. The Clove, the Trapps, Verkerderkill, Palmagat, Rondout, Rest Plaus, Kripplebush, Mombaccus, Dwaarskill, and Wallkill—are all Dutch in derivation (Hansen 1994, 1995; Ruttenber 1906: 140-170).

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Dutch and French Huguenots are the homes they built of native Ulster County limestone. These structures can be found today along the region's roadways, on remote farmsteads, or clustered together in the older villages. A number of historic districts have been designated in the region for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. They include the Stone Ridge Main Street Historic District, New Paltz's Huguenot Street Historic District, the Kripplebush Historic District, and the Rest Plaus Historic District. All contain a core group of buildings representing the architectural traditions of this period.

Within the region, initial Euro-American settlement patterns reflected the nascent economic and transportation systems. The primary economic pursuit was agriculture. Although early settlers were involved in the lucrative fur trade, it was apparent from the very beginning that the region’s “real riches” lay in the lowlands adjoining the Wallkill, and Rondout Creeks. Farms and settlements thus tended to cluster along these waterways. From the beginning agriculture was a commercial undertaking—at least for farms located in the more accessible areas of the valley. As early as 1683, wheat and other produce were grown for market, including trade with both New York and West Indies. During the 18th century, farmers in “the Butterfield” —a fertile band of farmland located near the villages of High Falls, Stone Ridge and Hurley—shipped cattle, butter, and cheese to other colonies, Europe and the West Indies (Davenport 1958: 4; Hansen 1995; Zim 1946: 58-59). In New Paltz, by the 1690s, wheat and flax were the staple crops, so much so that they were also used as a medium of exchange. The fields to the north of New Paltz, especially in an area called "Bontecoe," became famous for wheat production (LeFevre 1909: 190-191).

The milling of grain was a vital economic function in pre-industrial America. So too were the processing of timber and the fulling of homespun fabrics (Junior League 1974: 20). Thus, the presence of waterways that could furnish hydropower became another important factor determining the location of Euro-American settlements in the region. The unbroken forests and barrens of the Shawangunks fed numerous streams that flowed down the ridge's slopes, joining the Rondout, the Wallkill and the Shawangunk Kill (Batcher 2000: 5). The first gristmill in the Town of Wawarsing (originally part of the Town of Rochester) dates to 1702. It was constructed on the Vernooy Kill, a tributary to the Rondout (Terwilliger 1977:7). In what is now the Town of Gardiner, the earliest recorded settlement was at Tuthilltown where a mill was built upon the Shawangunk Kill in 1745. Other mills followed here later in the 18th century (Hasbrouck 1953; LoRusso and Vaillencourt 1987). Settlement in the Town of Crawford began in the mid-18th century, clustered around a series of mills on the Dwaars Kill and Shawangunk Kill (Ruttenber 1881: 412-413; Town of Crawford 2001). In the Town of Shawangunk, the availability of hydropower also played a major role in the settlement of Brunswyck, Dwaarskill and Wallkill (White 1988: 18-19). During this period, on the opposite side of the ridge, in the Town of Rochester, a cluster of mills developed on the Stony Kill and Peters Kill, tributaries of the Rondout that drained the Shawangunks' western slope (Sylvester 1870: 225).

Many of the region's early "service industries" —such as taverns, inns, blacksmiths, brewers—grew up along the early road system, especially at crossroads and fording places (Junior League 1974:20). Like mills, these facilities attracted small communities, often accompanied by a Dutch Reformed Church. In the narrow Rondout Valley, settlement was focused upon a single roadway, the Old Mine Road (corresponding to present day Route 209)—called also Esopus-Minisink Trail, the Great Waggon Path and King’s Highway—that connected the Delaware and Hudson Rivers. From the very earliest days of European settlement there was no direct overland route to the Hudson. Instead, the looming presence of the Shawangunk Ridge funneled trade and travel northwards towards Kingston and the Hudson River. Like most major roads of the time, the Old Mine Road followed an ancient Native American trail. Euro-American travelers used it as early as 1710. By the 1730s, farmers as far away as Pennsylvania and western New Jersey followed the Old Mine Road to the Hudson River at Kingston, where they loaded their produce on New York City-bound sloops (Lowenthal 1997: 127-128; Ruttenber 1881: 110; Zim 1946: 71).

In the Wallkill Valley portion of the region, several early roadways were oriented east/west to take advantage of Hudson River landings, such as Newburgh and Milton. The Bruyn Turnpike is said to date to the 1690s. Another road, in existence by the 1730s, linked what are now the villages of Galeville and Wallkill to the Hudson at Newburgh (White 1988: 18). By the late 1700s, before the hamlet of Gardiner existed, a road led from Tuthilltown directly to Modena (Hasbrouck 1953; LoRusso and Vaillancourt 1987). Opened in 1735, the principal north/south route was the Old Kings Road—running through Kingston, New Paltz, and "the Shawangunk Precinct" before finally reaching Goshen in Orange County (portions corresponding to present day County Route 7) (Ruttenber 1881: 110). Because the King's Road followed the west bank of the Wallkill River, New Paltz residents could connect with it only by crossing the Wallkill by scow (LeFevre 1909: 62-63). Another road was built on the east bank of the Wallkill River leading south by 1790 (corresponding to Plains Road and Route 208) (Halpern 1979: 16-17). A roadway leading from New Paltz to the Hudson (the New Paltz-Highland Turnpike) would not be established until the early decades of the 19th century (LeFevre 1909: 197)

The Shawangunk Ridge

Although settlement spread southwards down the region's two valleys, the Shawangunk Ridge remained largely uninhabited. There were no roads across it, only footpaths. Because of its size and rugged terrain, it would have represented a forbidding barrier for those settlers who sought to travel between the valleys. The threat of wild animals, unseen crevices, and hostile Native Americans was always present. Yet the ridge was also perceived as a place of refuge during times of conflict, as well as a source of mineral riches and valuable animal skins that could bring a family a small fortune. Archaeological evidence, documentary sources, and folklore suggest that surveyors, trappers, hunters, and inter-valley travelers spent time in the Shawangunks during the 18th century (Bevier 1846: 34; Fried 1981: 23-25; 1995: 37-39; 2000: personal communication; Harris 1998; Smith 1887: 116).

As the two valleys became more populated and good farmland increasingly scarce, a small number of families were drawn to the few locations on the Shawangunk Ridge where the soils could support agriculture. By the end of the 18th century, there were three communities on the ridge: Trapps Hamlet, within what is now the Mohonk Preserve; and the Mance and Goldsmith Settlements, near what is now Cragsmoor (Larsen and Fagan 1999; Terwilliger 1977: 6). The lack of roads leading to the valleys meant that the families living here were largely self-sufficient. Accounts from this period indicate that mountain residents raised sheep and grew flax to provide linen and wool. They raised cattle to provide leather for their clothing and equipment. Rye, barley and wheat were ground into flour at the nearest gristmill. Hunting and trapping were pursued for both sustenance and currency (Benedict 1907: 397-8). In time, mountain residents would come to depend upon forest-related industries for much of their livelihood. This would not occur, however, until the early 19th century, when markets for these products emerged.

Times of Conflict: The French and Indian War, the American Revolution

Due to reasons of topography and geography, portions of the region suffered significant casualties during both the French and Indian War (1754 to 1763) and the American Revolution (1775 to 1783). During these conflicts, the Shawangunk Ridge and its two adjoining river valleys lay along the frontier demarcating the division between wilderness and settlement. The isolated communities located here were thus very vulnerable to attack. Entering from the west, through the Catskill foothills, were a series of streams that provided access for various enemies based in western New York State and Pennsylvania. Running down the middle of the Rondout Valley was the strategically important Old Mine Road connecting the Hudson River to Pennsylvania. A line of blockhouses was constructed along this route during the French Indian War in order to protect the besieged settlers. Guerilla warfare, resulting in civilian deaths, became a feature of both conflicts (Anonymous 1907b: 103-113; Terwilliger 1977: 11-43).

Although there were no engagements here between the warring armies, sections of what is now the Town of Wawarsing became a Revolutionary War battleground of sorts—the site of several bloody skirmishes and raids. The presence of Continental Army regiments quartered at Fort Honk, near Napanoch, and of local militia stationed in Leurenkill, Napanoch, and Wawarsing, did little to deter attacks led by a force of Tories, Hessians, and Iroquois led by the famed Mohawk leader Joseph Brant. The deadliest raid was upon the settlement at Fantinekill, near present day Ellenville, in the spring of 1779. Those killed were mostly women and children. According to at least one chronicler of the incident, the Shawangunk Ridge played a major role in the event. Immediately following the attack, an alarm sent out to the surrounding communities resulted in terrified settlers scrambling up the ridge's western slope. Some managed to reach the Wallkill Valley. Others got as far as "Louis's Ravine" (also known as the Witch's Hole). Many were forced to spend the night on the mountain "which was full of people from both sides, with horns, hunting for them" (Bevier 1846: 34). Before the war's end, the region would suffer more attacks. These included murders and raids in Dwarkill in the Town of Shawangunk and on the ridge in 1780, as well as the destruction of the village of Warwarsing in 1781 (Bevier 1846: 38-42; Mauritz 1988: 100-102; Ruttenber 1872: 284-285). Some researchers speculate that the experience of the local settlers during the Esopus War led to the retention of stone construction, thereby saving many lives that might have lost during the Revolution (Junior League 1974: 19).

General George Washington did indeed sleep here. On November 15, 1782 he stopped for the night in Stone Ridge at the Wynkoop-Lounsbery House on his way to Kingston. His troops spent the evening at the Tack Tavern. Both structures are still standing (Hansen 1988: 17). Elsewhere in the region, a certain amount of mythology has accumulated concerning the Revolutionary War. One particularly persistent piece of local folklore combines two local legends. For many years it was widely believed that a Shawangunk Ridge lead mine supplied the Continental Army with ammunition. The mine in question was said to be the "Old Spanish Tunnel" reputedly excavated by Ponce de Leon's men during their search for the Fountain of Youth. The documentary record, however, indicates that government engineers worked the mine during the Revolution, but abandoned it upon concluding that the ore would be too difficult to extract (Heusser 1976a: 11-16; Terwilliger 1977: 120-121). Stories of lost mines, buried treasure, and caves filled with magical healing crystals remain part of the Shawangunks' cultural history to this day (LaBudde 1998a: 6; 1998b: 7; Harris 1998; Heusser 1976b; Smith).

ERA OF THE CANAL AND RAILROAD (The 19th Century)

Introduction

As sparsely settled and remote as the region may have been at the opening of the 19th century, its story was about to become interwoven with the story of the nation's industrialization. Beginning in the 1820s, the history of the region would be largely determined by the direct and indirect consequences of the American industrial revolution. Technical innovations in the forms of a canal and two railway lines reduced the time and increased the predictability of transporting products from the region to formerly distant urban marketplaces, especially New York City. The Shawangunk Ridge became the source of a seemingly inexhaustible flow of natural resources. Foremost among these were commodities related to the forests—hemlock bark, shingles, charcoal, cordwood and hoop poles. Even the very substance of the mountain—known as "Shawangunk grit" or "Shawangunk conglomerate"—was quarried, hewn into millstones, and shipped by railroad and canal. Limestone outcroppings from the ridge's flanks were mined and processed into cement. Agricultural practices in the valleys also changed. Milk, butter, fruit and berries shipped from local railroad depots arrived at New York City docks that very day. Towards the latter part of the 19th century, when industrialization and urbanization had transformed American cities, thousands of New York City residents traveled by railroad to the region's summer resorts, seeking inspiration and renewal in what they perceived to be a pristine rural environment.

The Delaware and Hudson Canal

The event that marked the region's entry into the industrializing world of the 19th century was the completion of the Delaware and Hudson Canal (the D&H) in 1828. Constructed to carry anthracite coal from the coalfields of northeastern Pennsylvania to New York City, the D&H represented an important phase in the history of American transportation. For the first time, technical advances made it possible to create navigable waterways by engineering existing rivers or constructing artificial channels such as canals. The choice for the D&H's route was determined by the fact that the Kittitinny Mountains and the Shawangunks impeded access to the Hudson River from the western interior. Just as the Old Mine Road had followed the Rondout Valley north to the Hudson at Kingston, so too did the canal. Once again, due to its geographic setting, the Rondout Valley succeeded in "capturing" trade and commerce that logically should have flowed elsewhere (Lowenthal 1997). As a result, portions of the region lying within the Rondout Valley were affected by the combined forces of modern transport and industry at least a generation earlier than those located within the Wallkill Valley. The latter remained overwhelmingly agricultural until the advent of railroads, a development that did not occur until the second half of the 19th century.

Although initiated as a means to transport anthracite to New York City, the canal presented what seemed to be limitless economic opportunities to many rural communities. Villages lucky enough to be located along the canal’s route thrived, their economies growing completely dependent upon the canal. Others sprang up almost overnight, owing their existences to the canal. Within the region, these self-described “canal towns” included Ellenville, Napanoch, Port Hixon, Port Ben (East Wawarsing), Middleport (Kerhonkson), Port Jackson (Accord), Alligerville, High Falls, Lawerenceville, and Rosendale. Prior to the canal's arrival, many of these villages had been little more than crossroads carved out of the wilderness. Suddenly cheap transportation was available, opening markets for a wide range of local products and resources. From the slopes of the Shawangunks came lumber, cordwood, charcoal, shingles, hoop poles, and millstones. Agricultural products included fruit, grain, and flour. New factories opened along the canal’s route. Ellenville and Napanoch were transformed into industrial centers. Their products included pottery, axes, glass, iron, leather, paper, and cutlery. Support services for the canal included stores, hotels, boarding houses, taverns, and harness and blacksmith shops. A number of communities, especially Ellenville, developed boat-building facilities (Lowenthal 1997: 277; Sanderson 1974; Wakefield 1964; Zimm 1946: 53).

Population growth along the canal was—in the words of one historian—"astonishing" Lowenthal (1997: 213). Local industries, rather than the canal itself, drove this growth.

Industry and Development during the Canal Era

Perhaps the most significant industry associated with the canal was the manufacture of hydraulic cement, also known as Rosendale cement. Hydraulic cement was critical to the canal's construction because it was non-soluble in water. Initial construction plans for the canal called for transporting this product from Madison County in western New York State, the nearest known source of coralline limestone. The historical record remains vague, but due either to luck or the intervention of a geologist employed by the canal company, limestone beds discovered in the vicinity of High Falls and Rosendale in 1825 were found to produce a superior quality hydraulic cement. For the duration of the canal's construction, cement was supplied by works established in High Falls. In the following decades, a cement manufacturing district developed centered around Rosendale and High Falls. The various communities supported by the industry tended to cluster along the canal's route and near limestone outcroppings. Completely dominated by the industry, villages such as Rosendale, High Falls, Lawrenceville, Binnewater, Creek Locks, LeFevre Falls, Bruceville, Whiteport, Hickory Bush, and Eddyville became both populous and prosperous. The region's cement manufacturing factories went into a decline in the 1890s, finally eclipsed by the manufacture of the faster setting Portland cement. During the peak years, locally produced cement was used in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, the dry dock at the Brooklyn Navy York, the Croton Aqueduct, and the Capitol and Treasury Buildings in Washington, D.C (Gilchrist 1976; Hartgen Archaeological Associates 1981: 10-13; Lowenthal 1997: 58; Roberts 1977a: 5-8; Zim 1946:54-56).

Like the cement industry, the quarrying of millstones from Shawangunk conglomerate also developed as a result of the ridge's geological properties. The quarries were located on the northwestern slope of the Shawangunk Ridge, concentrated in a strip about ten miles long that extended from Kerhonkson to High Falls. The stone was brought of f the mountain on sledges, known as “stone boats.” Along the D&H canal, the main shipping centers were Kerhonkson, Accord, and Kyserike. Millstones were also shipped from the Wallkill Valley Railroad in Rosendale. Approximately 350 tons of millstones were exported from these towns each year. During the 19th century, most of the nation’s millstones came from the region (LaBudde 2002: 2-3; Snyder and Beard 1981: 21-23).

Owing their existence to the canal, as well as to Hudson River shipping (and later to the railroad) were a series of industries that entailed the exploitation of the region's forests. Perhaps the most widely dispersed across the region was the tanning industry, based upon the harvesting and processing of hemlock bark. During the 19th century, thousands of acres of hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) were destroyed. Ironically it was only the bark that was sought, not the tree. Hemlock bark contained tannic acid; a substance used in the process of treating animal hides to create leather. Once the bark was removed, the trees were left to die (Snyder and Beard 1981:20). A booming tanning industry had emerged in the Greene County Catskills as early as the 1820s. By the 1840s, having exhausted the hemlock forests that fueled it, the industry shifted its focus to the south, towards Ulster County's Catskill foothills and the slopes of the Shawangunk Ridge (Evers 1982:336; Haring 1931: 90).

Tanneries required enormous amounts of pure water to fill the countless tanning vats that were used in the process. By the 1850s almost every creek in the Rondout Valley hosted a tannery. There were tanneries at Wawarsing, Honk Hill, Samsonville, Lackawack, Napanoch and Ellenville. Walker Valley tanneries included those located near Jenkinstown on the Plattekill Creek, on the Shawangunk Kill near Pine Bush, on the Verkerderkill near present day Walker Valley, and another on the Wallkill River, opposite Springtown. Initially these facilities shipped leather from Hudson River landings. Later in the century, they were serviced by the Walker Valley Railroad or the Crawford Branch of the O&W. Although tanning ceased in the Greene County Catskills by the end of the Civil War, it continued in our region through the 1880s (Benedict 1907:399; Evers 1982:391; Hasbrouck 1953: 24, 30; 1959: 61; Ruttenber 1881: 419; Sylvester 1880:270-271; Town of Crawford 2001).

The tanneries attracted a new labor force to the region composed of German and Irish immigrants. The industry also opened up an entirely new source of income for residents of the ridge. In the spring and summer months many worked as “bark peelers.” Winter and autumn work consisted of hauling bark by sled to the tanneries, cutting new roads through the wilderness, and constructing housing and outbuildings to support the industry during the upcoming season (Haring 1931:99-101).

Canal records from the mid-19th century provide a glimpse of several other commodities harvested on the ridge, including charcoal, shingles, and cordwood (Lowenthal 1997: 277). Charcoal was used by blacksmiths and for the production of pig iron (Evers 1982: 237). Traces of 19th-century charcoal pits may still be seen in the woods at Mohonk Preserve and Minnewaska State Park Preserve. Early settlers at the Trapps Hamlet are known to have engaged in its production (Historical Perspectives 1991: 24; O'Neill and Larsen 2000: 2; Snyder and Beard 1991: 21). Shingle making (or "weaving") was also an important local industry. The place name “Shingle Gully,” given to a ravine located on the mountain's western slope just above Ellenville, suggests that local residents were engaged in this livelihood. Shingle weavers were often hermits or farmers who worked on a seasonal basis. They fashioned shingles from white pine and hemlock. Shingles from the mountain were probably sold commercially to dealers in the Rondout Valley. Saegers Flats, located on the Verkerderkill in the Sam's Point Preserve, owes its name to John Saeger, a local shingle weaver active in the mid-19th century (Botsford n.d). Cordwood was another commodity harvested on the ridge. Much of this was probably marketed to Hudson River brickyards (Evers 1982: 562; Wakefield 1964: 48).

Hoop pole production and sawmilling are two local industries that developed in the wake of the destruction brought about by the tanneries. As one local historian observed, “the sawmill followed the barkpeelers” (Benedict 1907: 399). Numerous water-powered sawmills soon appeared along the mountain streams, processing not only the discarded hemlocks but also spruce, pine, and hardwoods (Evers 1982: 441). The hemlock lumber was coarse and not easily worked. There was a market for it, however, in the construction of wharves, barns, outbuildings, plank roads, and ice houses (Evers 1982:441; Haring 1931: 76-77, 94-95). An immense amount of milled lumber and timber was shipped on the canal between 1836 and 1866 (Lowenthal 1997: 277). The sawmills of the Rondout and Wallkill Valleys were so ubiquitous that local historians seldom bother mentioning them. Other sawmills were located on the ridge, close to the source.

The stands of hemlocks did not always replace themselves in the newly sun-filled clearings left by the tanning industry. Instead, hardwood saplings often appeared in their place. This became the impetus of a local hoop manufacturing industry. Wooden hoops were fashioned from saplings and used to bind kegs, casks, and barrels. Beginning in the 1840s and 50s, and reaching its peak in the late 1880s and early 90s, the industry is said to have shipped 50 to 60 millions hoops out of the region annually. At one time, the largest dealer of hoops in the country was located in Ellenville, shipping hoops all over the world (Ellenville Journal 1939; Evers 1982: 441; Haring 1931:110). On the eastern face of the ridge, hoop poles were produced by the residents of Trapps Hamlet for use by the Rosendale Cement industry or brought to Gardiner to be bartered in exchange for clothing and other goods (Hasbrouck 1953: 39; O'Neill and Larsen 2000:2). The Hamlet of Kripplebush, in the Town of Marbletown, was another important center for hoop making. Towards the end of the 19th century, hoop making and shingle weaving collapsed as new technologies rendered these livelihoods obsolete (Evers 1982:441; Hansen 1994; Haring 1931:110).

Areas of the region that lay beyond the canal's influence remained largely agricultural. This was especially true in the Wallkill Valley where the few existing local industries flourished as result of hydropower availability rather than access to markets. New Paltz, which experienced little industrial development during much of the 19th century, was rivaled by Springtown, its neighbor to the northwest. In the early part of the century, the main route south from Kingston was routed through Springtown rather than New Paltz (present day Springtown Road). Springtown became an important stage stop. Herds of cattle and sheep passed through on their way to market at New York City and Philadelphia. The village was also the center of a long established dairying industry (Halpern 1979:20; Hasbrouck et al. 1959: 79-80; LeFevre 1909: 203). Gardiner would not come into existence until the arrival of the Wallkill Valley railroad in the early 1870s (Hasbrouck 1953:42-46). The region's only other population center in the Wallkill Valley was the village now known as Wallkill (previously known as the Basin, Bruyn's Mills, Reeveton, and Shawangunk). Hydropower supplied by the Wallkill River supported grist and saw mills, a paper mill, a distillery, and a spoke factory. Significant industrial development in the village, however, awaited the coming of the railroad (Mabee 1995: 21)

Growth in the Wallkill Valley portion of the region would be slow until the local road system was improved. The closest Hudson River landings lay at least ten to fifteen miles away. In the pre-railroad era, the only transportation options for access to shipping points such as New Paltz Landing, Milton, and Newburgh, were stagecoach or wagon travel over deeply rutted dirt roads. The main route westwards was the Newburgh and Cochecton Turnpike (also known as the Cochecton-Cahoonzie Turnpike), chartered in 1801 (corresponding to present day Route 17K). Transecting the southern margin of the region, it linked the Hudson River landing at Newburgh with the mountainous interior of Sullivan County before terminating at Cochecton on the Delaware River. A superior roadway in its time, its traffic supported a number of the region's communities, including Bullville in the Town of Crawford (Ruttenber 1881: 112; Town of Crawford 2001). The Lucas Turnpike, originally called the Neversink Turnpike, was also conceived as a route that would open up the wilderness of Sullivan County. Promoted by Judge Lucas Elmendorf of Kingston, it was chartered in 1807 and never fully completed (Schoonmaker 1888: 408-410; Zim 1946:75).

Crossing the ridge remained a difficult undertaking until the middle of the 19th century. Traveling from the Wallkill Valley to the Rondout Valley entailed threading one's way via a network of connecting roadways and footpaths. After about 1824, travelers from the Town of Shawangunk could follow a series of roads to the various mountain top settlements. From here, the North Gully Road led precipitously down to Ellenville (Hakam and Houghtaling 1983: 11). Historic maps indicate that by 1799 a roadway or series of roadways connected the Wallkill Valley to the vicinity of the Trapps and Clove Valley (Larsen 1999:18). Further north, another road, built in 1825, corresponding in part to present day Mountain Rest Road, crossed the ridge linking the communities of Canaan and Butterville to Alligerville (Halpern 1979:18).

Routes across the mountain, linking Ellenville to Newburgh and New Paltz to present day Kerhonkson, were finally completed by the 1850s. Initial construction of the Newburgh-Ellenville Plank Road began in 1849. Running along an alignment that would later become Route 52, it passed directly through Pine Bush and was largely responsible for the initial growth of that community. The road was built of rough hemlock planks nailed to sleepers that were laid on the ground. It was thirty-two miles long, with five tolls. In 1869, maintenance of the now rotting planks stopped and the road was allowed to revert to mud and dirt (Ellenville Sesquicentennial Files n.d a; Ruttenber 1881: 419; Terwilliger 1977: 76-76). The New Paltz -Wawarsing Turnpike, which crossed the mountain between New Paltz and Kerhonkson, was completed in 1856. It was a toll road, running from the bridge over the Wallkill at New Paltz, past the present Smiley Gate House, westwards through Trapps Hamlet, and finally terminating in Kerhonkson at the D&H Canal. During the 1850s it was filled with farmers and drovers taking their produce and cattle to Hudson River landings. Anyone wishing a night's lodging could stay at Ben Fowler's hotel and tavern, located just south of Trapps Hamlet. The Turnpike's backers hoped that by connecting it with roads extending west into the Catskill foothills, such as the Lackawack Turnpike and the Napanoch-Denning Plank Road, the New Paltz-Wawarsing Turnpike would draw business away from the D&H Canal. This, evidently, was not to be as the Turnpike went bankrupt in 1861 (Larsen and Fagan 1999: 8; Elting Memorial Vertical Files n.d.).

The Arrival of Railroads

The Wallkill Valley Railroad was completed as far as New Paltz by 1870. The New York and Oswego Midland Railroad (afterwards the New York, Ontario and Western Railroad or "O&W") also reached the region at this time—one branch extending as far as Pine Bush by 1868 and another branch arriving in Ellenville in 1871. A new era in the region's history had begun. To say, however, that the railroads "replaced" the canal simplifies a lengthy and complex process. The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company had not only availed itself of the new technology represented by the railroads but was a leader in incorporating steam locomotives into the business of transporting anthracite coal. The advantages of railroad transport were inescapable and by the late 1850s the D&H had begun investing in railway lines that serviced its Pennsylvania coalfields. Yet the D&H kept the canal in operation, possibly as a means to regulate railroad rates. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s maintenance was minimal, representing, in effect, the canal's death sentence. Finally, in 1898, the D&H signed an agreement with the Erie Railroad to transport its entire output of coal. In that year, the last canal boat carrying coal to the Hudson passed through the region. Local communities attempted to keep the canal viable but in 1911 the last operating segment (High Falls to Eddyville) was abandoned (Lowenthal 1997: 225-276).

Although the region's railroads represented yet another 19th-century technological breakthrough, they did not truly belong to the same category of transportation as the D&H. The D&H Canal Company recognized and exploited the region's economic potential but its primary objective was carrying a single commodity—anthracite coal—from the Pennsylvania mines to tidewater. The cost/benefit calculations of that era suggested that the region could not have supported a canal on its own. Geographic expediency, rather than economic considerations, brought the canal to the Rondout Valley (Lowenthal 1997: 84). The impetus for the railroads, however, came from the communities themselves, inspired by the success of railroads elsewhere, and "clamor[ing] for a direct link to the great metropolis to the south" (Helmer 1959: 1).

Just as the canal had spurred the development in the Rondout Valley and along the western slopes of the Shawangunks, the Wallkill Valley Railroad brought new industries and livelihoods to the Wallkill Valley and to the Shawangunks' eastern slopes. Foremost among these were dairying, fruit growing, and tourism. Because it was the first railroad in Ulster County, its route assumed special significance. The promoters of the Wallkill Valley Railroad were local politicians and businessmen—led by some of the leading citizens of the Towns of New Paltz and Gardiner—and the alignment reflected their aspirations for the region. Many of the towns along the route issued bonds thus assisting in the railroad's capitalization. The line began in Orange County, at Montgomery, the northern terminus of an Erie Railroad branch line that extended from Goshen. From this connection, trains traveled south to Jersey City where ferries crossed the Hudson to Manhattan. Extending north from Montgomery, the railroad followed a route that took it through the villages of Walden, Wallkill, Gardiner (which came into existence only with the advent of the railroad), Forest Glen, and New Paltz. After some debate, it had been decided to route the train along the east side of the Wallkill River at New Paltz, which was the center of population and business. On December 20, 1870, an all day celebration was held at New Paltz in honor of the railroad's opening. Two years later, on April 6, 1872, another celebration was held in Rosendale, marking the opening of the enormous bridge that carried the railroad over the Rondout River, to its terminus in Kingston. At Kingston there were connections to Hudson River shipping, and finally in 1883, to the newly completed West Shore Railroad, which provided a direct link to Manhattan via the ferries from Weehawken, New Jersey (Mabee 1995: 9-26).

The New York Ontario and Western Railroad (the O&W), the line that serviced the Rondout Valley, was constructed as an Ulster County branch line of the New York and Oswego Midland. The latter was conceived as an outlet for a vast area that included Orange County, portions of the Catskill Mountains in Sullivan and Delaware Counties, as well as areas lying to the north and west of Catskills. As constructed, the railroad extended from its terminus at Oswego on Lake Ontario, to Weehawken on the Hudson River, opposite New York City. Emblematic of this railroad's ambitions and of the technological advances that had occurred since the construction of the D&H Canal, was the completion in 1871 of a tunnel drilled through the base of the Shawangunks near Wurtsboro. The railroad's mainline crossed the Rondout Valley in Summitville and headed west into Sullivan County. One branch line, terminating in Pine Bush, was completed in 1868, and another to Ellenville was completed in 1871. By 1902, the O&W had built track extending between Port Jervis on the Delaware River to Kingston on the Hudson River, thus duplicating the route of the nearly extinct D&H Canal (Helmer 1959: 1-85; Ruttenber 1881: 122).

The Rise of Tourism

Since at least the 1820s, affluent city dwellers sought escape from the discomforts of summer by retreating to country resorts. As the population of urban centers swelled during the 19th century, the public's perception of nature underwent a transformation. The wilderness ceased to be a source of dread and was now considered picturesque. These attitudes took on a spiritual aspect evident in the literature and painting of the period. This new American romanticism found its fullest expression in the paintings of the Hudson River School. Although the Catskills were a favorite subject of such painters as Thomas Cole and Asher Durand, the Shawangunks too became a focus of aesthetic and spiritual contemplation. Durand and other well-known artists including Stanford Gifford, Jasper Cropsey, and Jervis McEntee, traveled in the Shawangunks during the 1840s and 50s, producing paintings and drawings here (Buff 1982: 3-5; Novak 1988; Weiss 1987). In time, an artists' colony—Cragsmoor— would develop on the top of the ridge near Sam's Point and the community of Evansville.

As would be expected, the initial appearance of resorts for summer guests in the Shawangunks coincides almost exactly with the arrival of the railroads. The region was ideally situated for tourism—close to New York, serviced by two railroad lines, with the dramatic and scenic Shawangunks at its heart. The first hotels to open here during this era—the Mohonk Mountain House in 1870, the Mountain House at Sam's Point in 1871, the Mountain House at Lake Minnewaska in 1878, and the Mt. Meenahga House on the ridge overlooking Ellenville in 1883—catered to guests who valued the Shawangunks' scenic beauty. Although forests directly adjoining the hotels were being clear-cut for tannin bark and timber, landscaping at the hotels featured meandering carriage roads and vistas opened to create breathtaking views of the valleys and the distant Hudson. Also reflecting a newly romantic response to the Shawangunks was the architecture and setting of the hotels as well as their Native American names (not necessarily indigenous to the region).

The main buildings at Mohonk and Minnewaska were perched at the edge of

cliffs overlooking the lakes. At Sam's Point, the rear wall of the

building was composed of the cliff face itself. In

an effort to preserve a wilderness landscape and to become

self-sufficient, the Smiley family, owners of the Lake Mohonk and Lake

Minnewaska's Cliff House and Wildemere, embarked upon an ambitious

program of land acquisition. The more than 17,000 acres they purchased

included agricultural lands

and hemlock forests, as well as remote ravines and ridge tops

previously

inhabited by only moonshiners and fugitives (Botsford n.d; Burgess

1980:

15-23; Child 1871; Historical Perspectives 1991: 25; Snyder and Beard

1981:

26-31; Terwilliger 1977: 94-97).

indigenous to the region).

The main buildings at Mohonk and Minnewaska were perched at the edge of

cliffs overlooking the lakes. At Sam's Point, the rear wall of the

building was composed of the cliff face itself. In

an effort to preserve a wilderness landscape and to become

self-sufficient, the Smiley family, owners of the Lake Mohonk and Lake

Minnewaska's Cliff House and Wildemere, embarked upon an ambitious

program of land acquisition. The more than 17,000 acres they purchased

included agricultural lands

and hemlock forests, as well as remote ravines and ridge tops

previously

inhabited by only moonshiners and fugitives (Botsford n.d; Burgess

1980:

15-23; Child 1871; Historical Perspectives 1991: 25; Snyder and Beard

1981:

26-31; Terwilliger 1977: 94-97).

The entire region benefited from the development of tourism in the 19th century. In the Rondout Valley, the relationship between the railroads and the growth of the resort industry went beyond service and schedules. Trains were named after well-known mountain destinations. Construction materials for hotels were hauled for free. Beginning in 1880, realizing the enormous potential of passenger service of summer vacationers, the O&W started publishing "Summer Homes," a promotional guide to the region's hotels and boarding houses (Helmer 1959:51, 67). Providing some sense of the scope of local tourism, 1901 listings for the Ellenville-Cragsmoor area alone contained approximately forty establishments (Terwilliger 1977: 285-286). Mohonk Mountain House and the hotels at Lake Minnewaska dominated the hotel trade in the Wallkill Valley throughout the second half of the century. In the 1880s, stagecoaches operated by the hotels crowded the depots to await arriving trains. During the summer months special trains carried passengers up the Hudson River to Kingston on the West Shore line, where they could transfer to non-stop Wallkill Valley Railroad trains to New Paltz. In 1887, an extra siding was installed at the New Paltz depot to accommodate travel to the hotels. Local newspapers reported that the depot's business was "immense" due to the mountain houses. Guests seeking more humble accommodations also arrived by train. Smaller hotels and boarding houses were located in almost every village along the Wallkill Valley line (Mabee 1995: 84-89).

The Shawangunk Ridge

The popularity of the Shawangunks as a summer retreat also affected ridge top communities such as Trapps Hamlet and the settlements above Ellenville. After the construction of the New Paltz-Wawarsing Turnpike, the Trapps Hamlet had become a small but thriving community with a hotel, store, schoolhouse, and chapel (Larsen n.d.: 2). For much of the 19th century, its residents gained their livelihoods by pursuing a seasonal array of occupations. As itemized by Larsen (n.d.: 2) these included:

"…blueberry and huckleberry picking; nut gathering; charcoal making; moonshine making; maple sugaring; forest-fire fighting and fire look-out; hunting; guiding and trapping; subsistence farming; hoop pole making for barrels carrying Rosendale cement; tan bark cutting; logging and sawmilling; and stone cutting and millstone quarrying..."

After the 1870s, jobs at the Minnewaska and Mohonk resorts became available. Trapps residents built many of the carriage roads surrounding the hotels. Towards the end of the century, most sold their land to the Smileys and left the mountain forever (Larsen n.d.: 2).

The collection of settlements on the ridge above Ellenville (the Mance and Goldsmith Settlements and Evansville) had become less isolated during the first half of the 19th century. The Old Gully Road was completed in 1824. By the 1850s, the Ellenville-Newburgh Plank Road crossed the mountain at Evansville. As at Trapps Hamlet, forest-related industries occupied a major place in the local economy. In 1834, an establishment known as "the Mountain Hotel" had been built in what was to become Cragsmoor. It serviced the lumbering trade. Textile production was also important. Farm families kept flocks of sheep and grew flax. Women used looms to weave a variety of wool and linen products. At least one local barn devoted its upper floors to a weaving room where carpets were made. Local residents were also furriers, hatmakers, and beekeepers. The mountain was famous for its potatoes and maple sugar. As described above, with the advent of a summer community at Cragsmoor composed of artists and wealthy city dwellers, many local farmers sold their land or turned to supplying the newcomers with produce and services (Botsford n.d.; Hakam and Houghtaling 1983; McCausland 1945: 42-44).

Agriculture in the Age of Railroads

For farmers on both sides of the mountain, accessibility to railroads was a virtual guarantee that their dairy products and produce would reach the New York City market without spoiling. The railroad had arrived just in time. In a region dependent upon the canal and ten to fifteen mile trips over dirt roads to Hudson River landings, competition from the west had begun to take its toll (Mabee 1995: 9). An 1862 report from the New York State Agricultural Society noted that:

"Pork, beef, and grain were formerly exported to a great extent; our farmers have become convinced, however, that we cannot successfully compete with the fertile west, except in the production of such articles as cannot be transported by railroad" (LeFevre 1862: 403).

Several years into the railroad's operation, however, agricultural production in Ulster County had been transformed. The fields surrounding New Paltz were filled with new orchards. Visitors reported peach, pear and cherry trees, vineyards, and acres of berries including currants, strawberries, blackberries, and raspberries. New Paltz was now "a great fruit producing town" (New Paltz Independent 1883). The village of Gardiner, a community born with the railroad, was now the preferred shipping depot for about 30 local growers. Ancillary industries such as cold storage and fruit drying facilities were in operation, providing employment as well as protection from the growing season's vicissitudes (New Paltz Independent 1878). As noted by historian Carleton Mabee (1995:22), the railroad promised more than a speedy delivery to the market, it also provided protection for produce in the form of daily ice-cooled railway cars that delivered the fruit direct to waiting New York City dealers.

On both sides of the ridge, railroads and their promise of year round access to New York City markets, drew many local farmers into dairying. As with fruit growing, a milk production infrastructure grew up paralleling the railroad lines. Creameries were established adjacent to the depots at Bullville, Thompson Ridge, Pine Bush, Wallkill, Gardiner, New Paltz, and other smaller communities. Not only was milk processed and shipped from these plants, but butter and cheese were also produced. On the Wallkill Valley Railroad line, "milk trains" traveled north to Kingston. Here, the milk was transferred to the West Shore line for shipment to Weehawken, New Jersey, where it traveled to Manhattan docks by ferry. Milk shipped in the afternoon in the Wallkill Valley was in New York City households by the following morning (Mabee 1995: 90-94). The most famous dairying enterprise in the region was the Borden Farm, located in Wallkill. In 1881, members of the Borden family (owners of the Borden Milk Company) chose the village as the site of their 2000-acre home farm and condensed milk factory (Mauritz 1988:41-42).

On the ridge, harvesting of certain vegetation was an integral component of many residents' livelihoods. The gathering and distilling of wintergreen and huckleberry picking were two of the more important occupations. Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), which grows in the mountain's many shaded and moist ravines, was used for flavoring and for medicinal purposes. Its leaves were gathered and brought to local "stills" where it was converted into oil. Stills are documented during the second half of the 19th century near Trapps Hamlet "on the Peters Kill Road" and in Ellenville near the base of the mountain (Ellenville Sesquicentennial Files n.d.b; Historical Perspectives: 1991: 24; Kiviat 1988: 26; Sanderson 1968: 38-39)

While wintergreen oil production remained largely locally oriented, by 1871 huckleberries became one of the Shawangunk Region's major items of export (Child 1871: 139). Highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) and low-sweet blueberry (Vaccinium augustifolium) are among the species prevalent in the high elevation, fire-adapted vegetative communities typical of the Shawangunks (Lougee 2000: 9-12). As discussed above, exploitation of this resource may have been common among Native American cultures.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, local valley families probably visited the mountain to harvest berries for home consumption. Market-oriented huckleberry picking (the word "blueberry" being reserved for cultivated varieties) most likely originated in the 1850s when turnpike linking the mountain to communities in the valleys were constructed (Fried 1995: 146, 113-114). Harvesting for the local market began as early as the 1860s (Fried 1995: 113). The railroads, though, created a much larger market than had ever before existed. "The Patch" extended from Lake Mohonk to Sam's Point and was "especially prolific by the shores of the lakes." Huckleberries found their way to New York City on the Wallkill Valley Railroad (and then down the Hudson on "the Rondout Boats") or on the Rondout Valley's Midland Line (later the O&W) (New Paltz Independent 1877). By 1879, mid-July "huckleberry trains" had been introduced and pickers could sell through agents directly to the New York City markets (New Paltz Independent 1879).

At some point in the late 19th century, semi-permanent encampments developed in the vicinity of Sam's point. An 1899 map shows at least three separate huckleberry picker camps immediately west of Lake Maratanza (Smiley 1899). Like the Native Americans before them, the huckleberry pickers manipulated the local ecology by setting fires in order to increase yields. This particular Shawangunk Ridge lifeway continued—complete with yearly fires—well into the 20th century.

THE REGION IN THE 20TH CENTURY

Introduction

During the first half of the 20th century, the region's economy followed patterns established by the end of the previous century. Although many of the livelihoods based upon the natural resources of the Shawangunks slowly disappeared, agriculture and tourism remained mainstays of the local economy. Wallkill and Ellenville were the region's industrial centers, Napanoch the site of a large state prison, and New Paltz the site of a college for training teachers.

Tourism

The mountain resorts that had opened for business in the 19th century continued to prosper. These included the Mohonk Mountain House, Lake Minnewaska's Wildmere and Cliff House, Yama Farms, Mount Meenahga, and the various boarding houses and inns at Cragsmoor. Hotels catering to Jewish families had begun to appear in the Rondout Valley in the first decade of the 20th century. These were owned and operated by immigrants from Eastern Europe and Russia who had come to Ulster and Sullivan counties drawn by the belief that farming was a viable alternative to urban sweatshops. Because much of the land that they had purchased was unproductive, the practice soon developed of taking in paying boarders during the summer months. Some of these small boarding houses eventually grew into the famous "borsht belt" hotels of the region, such as the Nevele and Fallsview Hotels in Ellenville. Along side them were countless small bungalow colonies. Several of the villages along the ridge's western slope soon developed sizeable Jewish populations (Terwilliger 1977: 90-119).

Agriculture

Farmers in both the Rondout and the Wallkill Valleys pursued fruit growing and dairying. In both valleys, however, farm populations were declining. Especially hard hit were the Towns of Shawangunk and Gardiner (Mabee 1995: 109). Beginning in the 1920s, apples would begin to supplant other fruit as the county's dominant crop. After World War II, the floodplains of the Rondout and Wallkill came to be devoted almost entirely to the cultivation of sweet corn (Dowaliby 1977; Kelly 1981). Local dairy farmers, however, were finding it difficult to operate in the face of low milk prices. This trend began in the 1920s and 30s and was marked by the closures of many creameries (Mabee 1995: 95).

The Automobile Age

Beginning at the turn of the century, New York State began a program of road development in the region. This entailed the construction of entirely new roads and the modification of existing roads. The effort marked the initiation of a statewide policy that would create a transportation infrastructure benefiting automobiles, buses and trucks (Mabee 1995: 109). Newspaper accounts from the years 1906 to 1907 indicate that much of this activity focused upon more populated areas such as New Paltz and Ellenville. Improvements to the Ellenville-Kingston Road (today's Route 209) were underway in 1921 (New Paltz Independent 1921). In the same year, the New Paltz-Highland Road became the first concrete road in Ulster County (Mabee 1995: 109). The Minnewaska Trail, today's Route 44/55, was built over the ridge, connecting New Paltz and Kerhonkson in 1930, replacing the old New Paltz-Wawarsing Turnpike with a more direct paved route. Much of the original turnpike alignment and many of the Trapps Hamlet homesteads were destroyed during its construction (Larsen and Fagan 1999: 17). Route 52, the other main highway crossing the ridge, was completed in 1936, replacing what remained of the Newburgh-Ellenville Plank Road (Terwilliger 1977: 85).

By the 1920s, automobiles had become so popular that the railroads began to falter. Families that had previously traveled throughout the region by wagon and train began to use private automobiles and buses. The first serious losses on the O&W occurred in 1925 (Helmer 1959: 121). It was only on the Catskill and Shawangunk segments of the O&W system, however, that ridership remained strong. Apparently the dangerous mountain roadways discouraged tourists from driving (Helmer 1959: 125). Between 1893 and 1931, the number of passenger riding on the Wallkill line declined from 500 to 35. In 1937, passenger service was discontinued (Mabee 1995: 108-112). The O&W held out until 1952 before turning exclusively to freight (Helmer 1959: 160-162). The O&W ceased operations in 1957 (Helmer 1959:166). Conrail, which now owned the Wallkill line, cut all regular service north of Walden in 1977 (Mabee 1995: 135).